The kind lady at the Lovasoa Museum, located in the same grounds as the Cultural Center https://www.facebook.com/Lovasoa4c where wonderful archives preserved by the Norwegian Mission Society in Antsirabe are nestled, indeed had a colourful and entertaining narrative to tell the city to my four little ones, whom I dragged around with me to construction sites and meetings as a trade-off for hours of fishing, horseback riding, pizza, and swimming. Even with my most pedagogical tone, I could never have kept their attention for so long. In fact, I found myself biting my lip and politely stepping away when she touched on themes too quickly without getting lost in the details and dates, so as not to spoil the mood with my pedantry. Honestly, it’s all a bonus, and leaving there, you’ll feel the satisfaction of having fed Culture in its rawest form into the mills of their young minds. The visit takes an hour, costs 500 Ariary per person, spans three levels, and no photos are allowed. You can also book a stay at this beautiful site : a home away from home really. https://www.lovasoa.mg/?fbclid=IwAR0Adtjo9_2ezcUsl_O66gIrTyEkPX_30BE3qFUB7yD3L8CG7Yy0Ps1z8Lg

This was precisely the purpose of our stay in their father’s family’s region of origin. An opportunity to gradually lay the foundations, understand their culture, their roots, and also to accompany Mom in her everyday work. I think they grasped the rhythm and intensity. Indeed these missions were our only opportunities to go on vacation since our definitive return to Madagascar in 2013. But honestly, I don’t really know Antsirabe. The city has always been a waypoint on the journey to the Deep South, which I often visited, and I am certainly more familiar with the neighborhoods of Tuléar than those of the capital of Vakinankaratra. It was really only when I went out with Tojo in my final year of high school at 18 years old *wink* that I discovered three streets and four buildings in the city—a total loss.

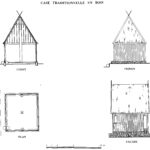

Thus, I learned, also from my readings on the city’s origin shaped by Norwegian missionaries, including Thorkild Rosaas, the builder of the thermal center and initiator of the city’s urban layout as early as 1872. If we project onto the architectural timeline of Madagascar (to be assembled but for now, it’s in my head): Antananarivo as early as 1826 James Cameron, a carpenter by trade, whose first building in Analakely was made of raw earth in competition with Jean Laborde for the attention of Queen Ranavalona I, had already introduced fired brick in his house in Ambatonakanga . Upon his return from exile in 1861, he nonetheless maintained the tradition of “living” by constructing the lovely Manampisoa pavilion in Creole pavilion style (Louisette told me about Creole architecture kinship even with the Rumah Adat, and I’d love to explore the historical twist of this import on a territory where this building morphology had been implanted for 1000 years in the form of trano kotona by Austronesia settlers). Subsequently, Ranavalona II made the freedom of other religions’ practices effective, primarily Christian proselytism, consequently lifting the ban on stone and earth in constructions in 1868, followed by the constructions of the LMS model of the Memorial Church and the tranovato of Ambatonakanga expanding to uphill Fianarantsoa.

But there is also the pre-fired brick period, for which we only have as documented landmarks the very indigenous houses still replicated in the 21st century, except for the very royal trano kotona supplanted by the trano gasy. Fashion effect, political dynamics, still, the survival of plant-based housing to this day, despite an adaptation to the disappearance of forest cover, the primary source of materials, remains an entirely unexplored area in construction techniques and even less so in Malagasy architectural literature (honestly this was a tough subject I taught for years due to the scarcity of content https://purplecorner.com/malagasy-wood-architecture/). Hence my shock upon discovering the Norwegian mission stations arrived by boat in prefabricated detached pieces as early as 1880. It shipped its first houses in Madagascar https://purplecorner.com/strommentraevarefabrik/ in order to make living conditions more comfortable in areas such as Menabe and Deep South. This discovery expands widely my research fields from the notion of techniques transmission to the materials flexible and available enough to be used in today’s living constructions. what about the Fantiolotse then ? https://purplecorner.com/planter-le-fantiolotsepour-mieux-enraciner-une-societe-durable/

I had somewhat shocked my interlocutor when I introduced these first houses, and in fact, it’s normal that we only know the first modern house in Antsirabe as a brick house, Rosaas House. And I even saw a glimmer in her eyes in anticipation of the sessions we would spend in the beautiful archive room on Stavanger Street, which naturally leads to Rosaas Park strangely surnamed nowadays Garden of Troubles something somewhat fascinating and troubling at the same time. some kind of omen of all the works and challenges ahead of one who is willing to dig further establishing grounds for a more sustainable architecture in Madagascar.

photos : from https://www.facebook.com/Lovasoa4c